I tag-teamed with my pastor on this morning’s message. This is what I had to say.

In the Neopagan Wheel of the Year, the Spring Equinox is a quarter festival called “Ostara.” The word Ostara comes to us by way of Jacob Grimm, who was a linguist as well as a collector of folklore and an editor of tales. Ostara is his name for the Germanic goddess that the 7th-century historian Bede called “Ēostre.” It’s from these two sources that contemporary pagans have constructed a goddess to celebrate in early springtime.

I say “constructed” rather than “reclaimed” because—beyond the two question sources cited above—there is no evidence for an Anglo-Saxon deity called Ēostre or a German deity called Ostara.

It is, of course, impossible not to notice similarities between the words Ēostre and Ostara and Easter and Ostern (the German word for Easter). Given that most of the Christian world uses some form of pascha—Latin for Passover—to name the time around Christ’s death and resurrection, it’s not surprising that a linguist like Grimm would be curious to figure out why the English and the people in his own country did not. But Grimm’s style of inquiry was more about making up stories and finding—or creating—evidence to fit those stories than following the evidence of his research wherever it led. So, Grimm’s fertility goddess is built upon one reference in Bede and a lot of wishful thinking.

None of this is to say that Ostara—the goddess or the holiday—is fake. There are experts who point out that there was plenty of room for a goddess like Ēostre in pre-Christian Britain. For example, in a journal article published in 2020, archaeologists Luke John Murphy and Carly Ameen posit that Ēostre might have been a deity with a small local following in Eastern England. In any case, Neopagans have found the idea of this goddess meaningful enough to build symbolism and celebration around her and, as Starhawk has said, “We belong to the oldest tradition of all: the tradition of making stuff up.” The very fact that so much has been made up about Ostara suggests that she fulfills a need, and it seems like the need she fulfills is the need for a deity who embodies the wild fecundity of spring.

When 19th-century philologists decided that hares are sacred to Ostara, they were thinking of Aphrodite. The natural historians of ancient Greece wrote that, because the hare was prized game, the species could survive only through prodigious breeding. This is one reason why the hare is a fertility symbol. The hare is connected with the moon in many cultures, and therefore also connected with the human menstrual cycle—another link with procreation. Most of the other animals commonly associated with Ostara are symbols of new life. Chicks and lambs are, of course, born in the springtime. Snakes represent rebirth because they shed their skin. Eggs are self-explanatory. Dairy products are often featured in Ostara feasts, as sheep and cows are producing large quantities of milk for their babies in the spring. All of this is to say that Neopagans have created a rich vocabulary of ways to greet the Spring and, for some, Ostara is the ruling archetype at the center of this celebration.

Making myths is a quintessentially human thing to do. All of us—at least most of us—long for a sense of meaning and connectedness, even if we have to create it for ourselves. April 1 is a significant day in my own personal mythology. My mom died on March 31 and… She took a long time to die. When she finally let go, my sister, our dad, and I ventured back out into the world after days and nights spent in the hospital. It was dark and cold and we were being pelted by freezing rain on the top deck of the parking lot where my dad’s car waited. And we were laughing, giddy from the release. Then we went home and went to sleep and woke up into a new and different world on April 1st.

It’s been 11 years, and my sister and I still recognize April 1st as a sort of New Year’s Day. I’m sure some of you know the stories about how April 1st was, once upon a time, New Year’s Day in much of Europe. Some of these stories are probably historically true. Maybe all of them are symbolically true. In any case, April 1st is now a day for foolishness.

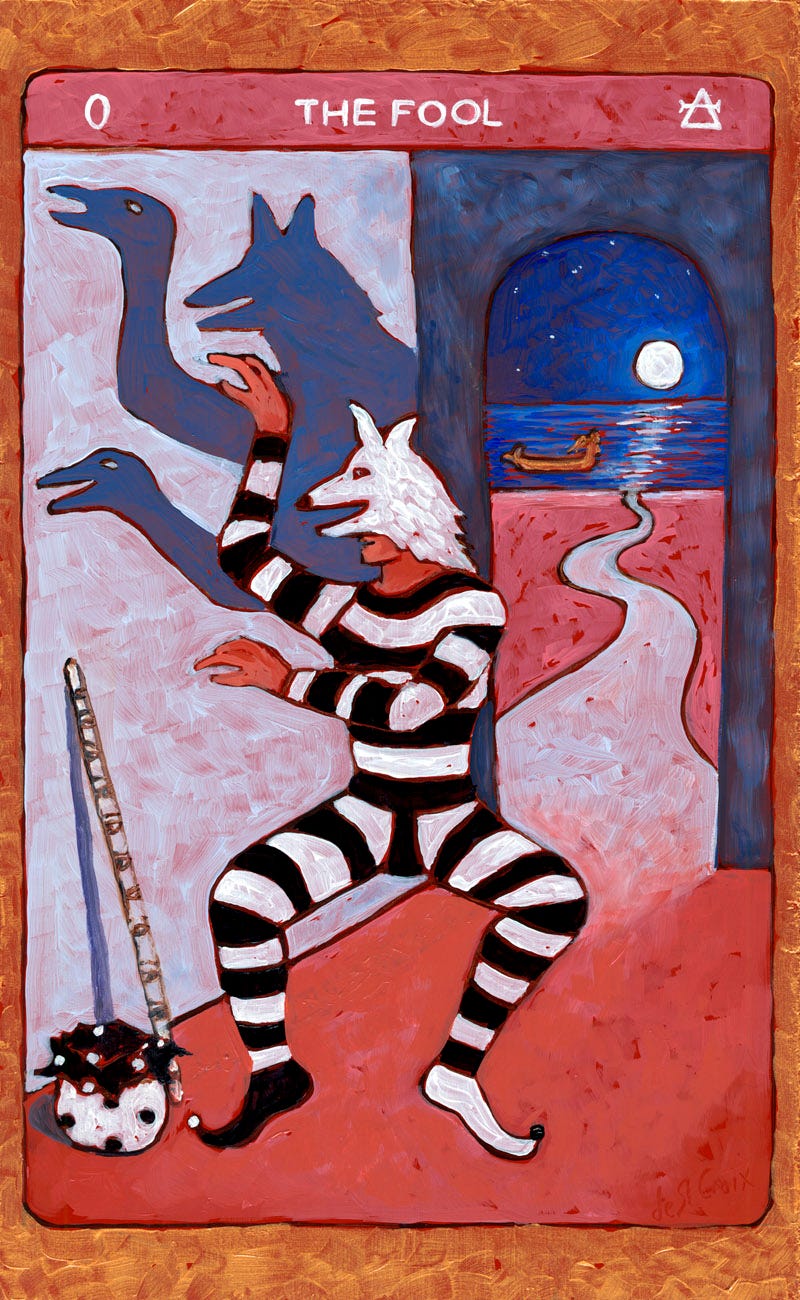

In Tarot, the Fool is card number 0. I see the Fool is an absolute beginner, someone too fresh and new to fear the unknown, too innocent to speak anything but the truth. Tarot’s Fool has a long and varied pedigree, one that encompasses figures no less daring but perhaps less innocent. Like Coyote, like Kokopelli, like Anansi the Spider, the Fool can be a trickster.

The trickster reminds us that we can only create something new by destroying what already exists. The trickster breaks the rules and, in doing so, the trickster makes space for something that has never existed before.

Is it a coincidence that animals associated with Ostara are also avatars of the trickster archetype? Is it purely accident that hares and rabbits are symbols both of fecundity and creative destruction? I can’t say, but I can tell you this:

In Ojibwe stories, Nanabozho—trickster, shapeshifter, and co-creator of the world—takes the form of a hare. Among the Cherokee, the rabbit is known both for its fertility and its craftiness. Bre’er Rabbit—the wily hero of stories people enslaved in the United States told each other—has roots in African folklore.

In Northern Europe, hares were associated with witches—both as familiars and as a form witches might take. In Irish lore, they are messengers from the Otherworld—fairy beasts and fairies in the shape of beasts. Fairies themselves are tricky, as likely to harm humans as to help them. Witches, of course, are similarly ambivalent. Sometimes they bestow gifts. Sometimes they toss you in the oven. Only a fool would trust a fairy. Only a fool would trust a witch.

But, sometimes, life asks us to be foolish. Sometimes life makes us foolish, whether we choose it or not. I laughed when I saw my first robin of the year. I laughed when I knew that my mom was finally dead. And, every day, I keep working—for my family, for my community—because I am foolish enough to believe that change is possible.

Which brings us back around to Ostara and to Easter. Whatever relationship these holidays might have to each other, they are both liminal moments, moments in which we anticipate what will be and imagine what could be. Moments in which change feels possible. And, sometimes, change requires a bit of foolishness—which we might also call hope or trust. Maybe during this season of rebirth and growth, it’s time for you to break some things. Maybe it’s time to act the fool and take a joyful step into the unknown.